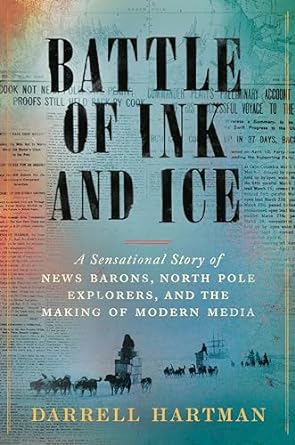

That title suggests a sweeping George R.R. Martin epic, no?

Don’t let the train of sled dogs on the cover get your hopes up, though —

despite the suave jacket photo of author Hartman (who

passingly resembles shameless Indiana Jones wannabe Don Wildman, host of my

Travel Channel guilty pleasure

Mysteries at the Museum), the draw here isn’t

“adventure”

per se.

In fact, Hartman treats the turn−of−the−century race between joyless

blowhard⁄public relations nightmare Wiliam Peary and charming fraudster⁄future FDR pardonee Frederic

Cook to “discover” the geographic North

Pole, which would be the main course in any other book, as a mere side dish.

In an unforgettable scene that would have provided a more conventional yarn its climax,

Peary’s traveling companion Matthew Henson unwittingly pulls off his hapless boss’s frostbitten

toes along with his sock — unforgettable not only for Peary’s blasé

reaction, but also in the way Hartman, in kind, recounts it so offhandedly (to hilarious

effect, I have to

say).

Hartman is

far more fascinated

with intrigue — not only between Peary and Cook, but between competing newspaper owners at

the dawn of modern media, who generate even juicier displays of backstabbing, bad

behavior, and cynical one–upsmanship. With the

New York Herald’s James Bennett

representing

the

yellow

journalism of the future Fox News and the

New York Times’ Adolph Ochs the more

measured approach of, er, the future

New York Times, a theoretically apolitical endeavor

of science and

exploration in fact divides the public on party lines: grumpy New

Englander Peary with the Roosevelt Republicans, the charismatic Cook with the Jennings Bryan

populist

Democrats.

Given that neither man

actually reached the pole, it’s one more reminder

that

for

many people, emotionally based arguments, things they “feel in their gut,” trump

scientific

evidence,

recalling

The Panic Virus, Seth Mnookin's superb 2011 account of the so−called

“vaccine wars,”

which observes some invest less credibility in a nerdily off−putting scientist spouting jargon than a

photogenic celebrity espousing quackery.

Perhaps because of that, I think Hartman

might

have crafted a more compelling book by sidelining the Arctic pioneers

and focused instead on early warring media scions learning how

to manipulate their reading public for power and profit.

Still, I admit laughing out loud at his best line, which comes

at the pivotal moment when various fed−up parties demand

the Arctic rivals supply their (apparently

falsfied and⁄or non−existent)

navigational data and Peary and Cook instead sling

ad hominem mudpies at each other: “The fur gloves were off now.” Macho!

B+Grade: B+